There truly is no article of clothing quite like the leather motorcycle jacket. No other item can scream “screw you!” and “trés chic” all at the same time. It’s impossible.

I might be biased, though, since I was pretty much born wearing a leather moto jacket.

This style of jacket has been an integral part of my identity for as long as I can remember. As I mentioned in my BlankNYC suede moto jacket post, my mom (who is an OG leather jacket-wearer from back in the day) was the one who introduced me to the moto jacket. Since then, I’ve had at least one version of it in my closet.

So, what’s the appeal of the leather motorcycle jacket? Is it because the jacket contains a harsh dichotomy in its fibers: it’s both inviting and repellent? Or is it because the jacket is such a timeless piece that looks like it could belong in any decade (because it actually has)? Perhaps its appeal is even partly because of it’s history of being worn by some of the true BAMFs in modern history.

The Style of the Leather Moto Jacket

The style of the leather motorcycle jacket has remained relatively unchanged for almost a century.

It was only when it became popular in mainstream culture that the jacket finally got changed. Nowadays, you can find leather moto jackets in a variety of cuts, colors, shapes, and sizes. Some with zippers, some without. Short jackets and long jackets. Jackets with lapels and jackets with no lapels. The possibilities are endless!

It’s, Like, Totally Popular

One of the most amazing things about the leather motorcycle jacket is its persistence. It’s one of the few fashion pieces that has gotten progressively popular throughout its lifetime, in spite of its sordid reputation.

Sure, there were periods when it was labeled as the garb of outlaws, vagabonds, and ne’er-do-wells, but no other article of clothing has dealt with so much adversity to make such a remarkable comeback.

Granted, it helps that the connotations and attitudes regarding the motorcycle jacket have really changed within the last few decades. While it’s now primarily viewed as a way to add a bit of edge to an outfit, it was once a signifier of where you belonged in society: in the outer fringes. If you saw someone wearing one of these, you were meant to run the other way.

The History of the Leather Motorcycle Jacket

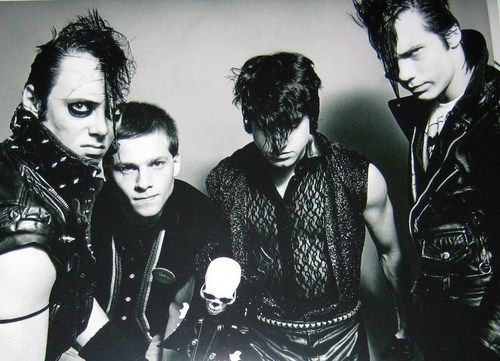

Marlon Brando in The Wild One, 1953.

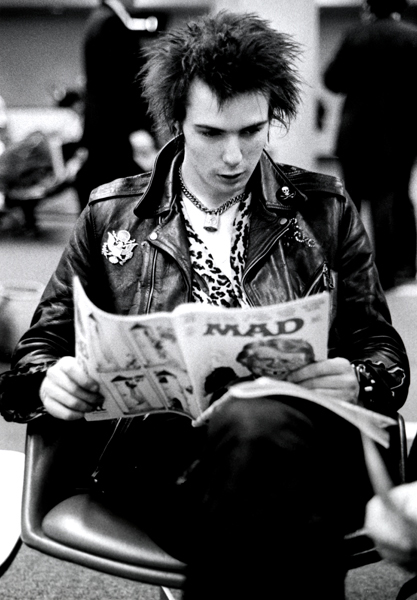

Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols, circa 1977.

It seems obvious because it’s in the name, but when considering the history of the leather moto jacket, you also have to take into account the history of the motorcycle. The image and connotations associated with the motorcycle (which, let me tell you, have historically not been good) are manifested in the wearable symbol that is the leather motorcycle jacket.

Because of this, I am primarily focusing on the social history behind the leather motorcycle jacket. Leather jackets as a whole is a topic deserving of an entire book which maybe I’ll write one day. Who knows?

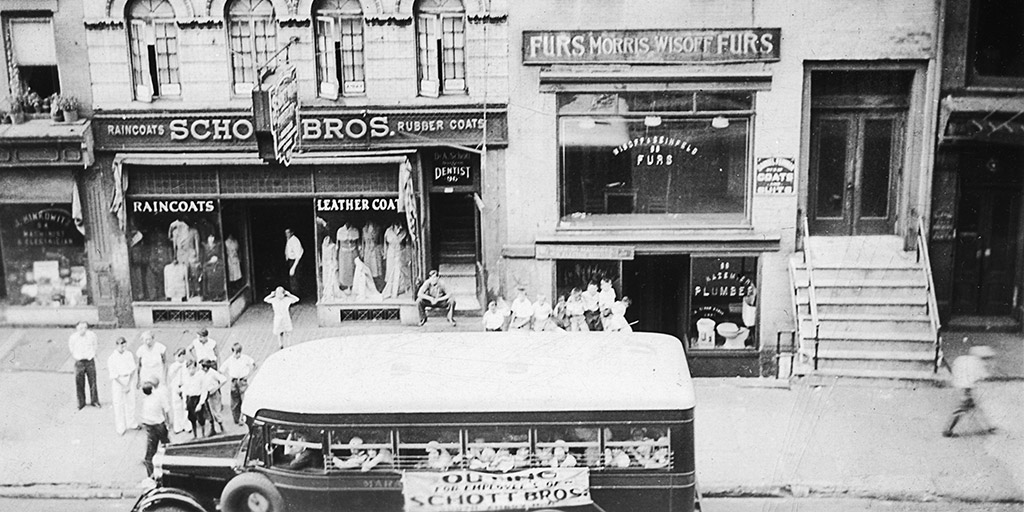

While the motorcycle jacket was an icon of intimidation, it’s as American as it gets; not only because of how its reputation has drastically changed as it has been accepted into the mainstream, but because it was invented by first-generation immigrants at the start of the 20th century. The inventors, Irving and Jack Schott, quite literally lived the “American dream.”

1920s-1930s: The Schott Brothers

The story of the leather motorcycle jacket appropriately starts in the basement of a tenement building on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Two brothers of Russian immigrants, Irving and Jack Schott, sat at a draft table. They were sketching furiously; drawing, erasing, and re-drawing with great zeal.

The Schott brothers were working on a design for a new leather trench coat. The brothers finally agreed upon a style, sewed the pieces of leather into a jacket, and off it went with the street peddlers who sold it door-to-door.

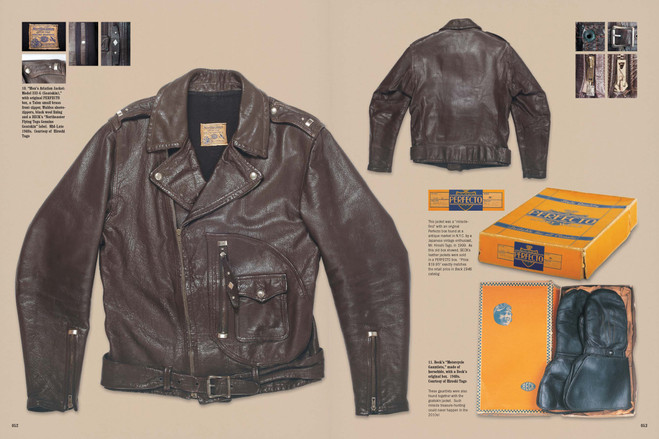

The Birth of the Perfecto

The leather trench coat that they had created was called the Perfecto, named after Irving’s favorite cigar company. It reached mid-thigh and had button enclosures and a tie around the waist, similar to a traditional trench coat.

The Schott leather trench coat was a financial success.

To further innovate upon their successful jacket, Irving Schott had a brilliant idea: add a zipper-front enclosure.

And, just like that, the updated version of the Perfecto was shortened by a few inches and now had a modern zippered front. This was the first time in the history of garment construction that a mass-produced jacket had a zippered front.

By this point, the Schott brothers were immensely successful and things only got better once they came into contact with the Harley-Davidson Motorcycle Company.

The Schott Bros. & Harley-Davidson

The Harley-Davidson Motorcycle Company, which was founded in 1903 by William S. Harley and Arthur Davidson, was proving extremely successful in post-WWI America.

The motorcycle that soldiers had driven during WWI soon became an integral part of their everyday life. Once they returned home, they wanted to retain that part of their service. The motorcycle represented freedom and adventure, a necessity once they returned to mundane civilian life.

A Problem & a Solution

Since these men were skilled motorcyclists, they knew that a spill every now and then was going to happen.

To protect themselves, early riders began wearing dungarees (blue jeans) along with a thick wool jacket to help prevent road rash. While the jackets provided superficial protection, the flimsy fabric ultimately did not protect the wearer from extensive damage. They also didn’t protect riders from wind and would puff up uncomfortably while they were riding. Riders could take a chance and wear a different cut of a leather jacket, however, these provided limited mobility to the rider.

The Schott Brothers saw this opportunity and leapt on it. Since they already manufactured a zippered leather trench coat, they tinkered with the design a bit to create the first leather motorcycle jacket.

Their new jacket, also named the Perfecto, had an angled zipper to not only block wind, but to also keep the jacket from being too stiff and bunching up on the rider like other contemporary leather jackets. The addition of zipped pockets allowed the rider to store whatever they needed without worrying about their stuff escaping during a ride.

Now, to us, the leather motorcycle jacket is anything but out of place. It’s one of the ultimate fashion items. But think back to the 1920s…how absolutely bonkers would these leather jackets have looked to the stuffy, well-groomed general public?!

The Schott Brothers, who were friends with the Beck family, one of the largest distributors of Harley-Davidson at the time, were able to sell them through their merchandise catalog. By 1928, the Schott Brothers were selling the first ever leather motorcycle jacket through the Becks’ merchandise catalog for $5.50 (which equals about $85 in today’s money).

The 1940s-1950s: From World War II to The Wild One

At the start of WWII, the Schott brothers had to halt the majority of their consumer production. They still created new jackets, though, it was for a very different clientele.

During WWII, the Schott brothers were contracted by the United States Armed Forces to assist with the design of their uniforms. The brothers designed and produced the bomber jacket for the U.S. Air Force, while also revamping the traditional design of the pea coat for the U.S. Navy. After WWII ended, the Schott company went back to business as usual.

Side note: it’s seriously crazy that one company created so many iconic fashion staples in just 20 years!

The Motorcycle in Post-WWII America

As soldiers returned home from WWII, many of them faced the same challenges that soldiers from WWI faced when they returned back to civilian life. In addition to having to reacclimatize themselves to regular jobs and family life, soldiers also had to revert back to civilian transportation methods. Just like in WWI, the soldiers of WWII had relied upon the motorcycle as one of their primary modes of transportation.

At the end of WWII, gas prices were extremely high and, as we know, cars of the time were anything but gas efficient. Because of this, soldiers bought motorcycles in increasing numbers once they returned home. By 1945, there were over 198,000 registered motorcycles in the United States.

While most motorcyclists in the 1940s were peaceful and only wanted to ride to escape their everyday life, there were others who rode to cause disruption, chaos, and to start fights. These riders debuted to a terrified public at the Hollister Rally of 1947.

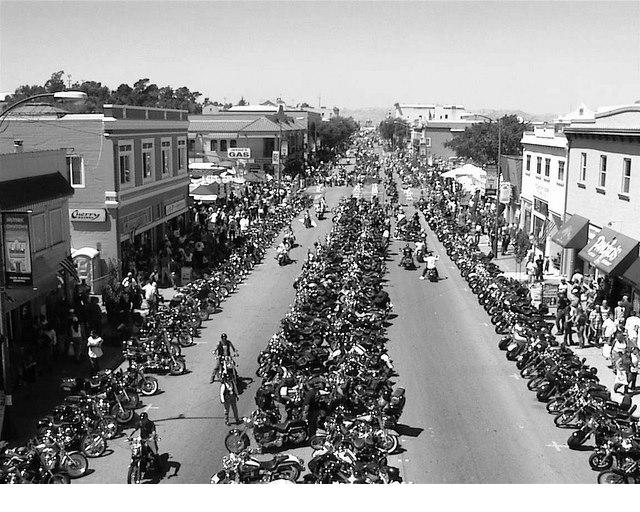

The Hollister Rally of 1947

Ever since the motorcycle rally at Hollister, California in 1947, which was sensationalized by the contemporary press, the biker acquired the “outlaw” image.

The organizers of the Rally, the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA), had created the event as a way for motorcyclists around the country to join together and unify. As with any large social gathering, though, there were a few bad seeds who did not have unity in mind.

A group of bikers arrived incredibly intoxicated and belligerent. They raced their bikes up and down the streets of the town of Hollister all day and all night. In addition to their raucous demeanors, they broke every traffic rule and also tried to start fights with anyone and everyone.

Because of this small group of hostile bikers, motorcyclists as a whole, were labelled as “lawbreakers,” “drunks,” and “vagrants.” Newspapers further decreed all motorcyclists to be “outlaws.”

Unfortunately, this image of the biker would only get worse with the creation of motorcycle gangs. And, yes, I’m talking about the Hell’s Angels.

Motorcycle Gangs from the 1940s-1950s

In addition to purchasing motorcycles, veterans also started motorcycle gangs to establish the camaraderie they had felt in the service. One of the most well-known motorcycle gangs, The Hell’s Angels, was formed by a couple of WWII veterans in 1948 in San Bernardino.

Even though veterans were purchasing a large amount of bikes, motorcycles still weren’t super popular in the late 1940s.

Because of this, accessing a motorcycle repair shop or a store to purchase the parts you needed would be difficult or almost impossible. Every person who drove a motorcycle, then, had to be self-sufficient. They had to be, as Randy D. McBee aptly put it, a “…’halfway mechanic’ because ‘something was going to break sooner or later’.”

This idea of complete autonomy, self-reliance, and independence was translated into sales. Between 1950 and 1960, the rate of registered motorcycles in the U.S. rose from 450,000 to 575,000. This image was also projected onto the leather motorcycle jacket. It was (and still is!) a symbol of freedom and autonomy.

Though, not everyone who rode a motorcycle wore a leather jacket….

The West Coast Bob vs. the Eastern Marcel

In post-WWII America, men’s apparel for riding motorcycles primarily fell into two categories– the Western Bob (or West Coast Bob) and the Eastern Marcel. These two styles were so different from one another that you could identify who was from which group instantly. And, of course, that was the whole point.

The Eastern Marcel

When you think of a traditional biker, you probably envision a leather-clad rider complete with heavy, ass-stomping leather boots, a pageboy hat, and shiny, silver studs freckling their ensemble.

If you do, then, you’re picturing the Eastern Marcel.

The Eastern Marcel was the nickname bestowed upon motorcyclists who hailed from the East coast and the Midwest and dressed primarily in leather.

Safety First!

As I mentioned previously, the attire worn by early motorcyclists was designed with the safety of the rider as the primary goal.

As such, everything that the Eastern Marcel wore was functional: the leather pants and jacket were durable; silver studs on the leather jackets not only protected them from particularly nasty spills, but also provided increased the wearer’s visibility to other motorists on the road; and the thick, heavy boots protected their feet in case any heavy machinery fell on them.

As noted in Born to Be Wild by Randy D. McBee, “…the bright spots and showy clothing are safety factors in that motorists see motorcycles more easily if the motorcyclist is dressed in shiny leather studded with chrome….”

In addition to safety, McBee notes that the leather served a super functional purpose as well: “…road dirt and grease and oil can be cleaned from leather pants and jackets where it would stain more ‘acceptable’ clothes.”

The West Coast Bob

The apparel of the West Coast Bob was an entirely different matter.

Instead of studs and leather, these dorks would wear loafers, khaki pants or jeans, and cardigans or light, non-leather jackets when they went out for a ride. These articles of clothing worn by the Western Bob’s severely lacked in proper protection from a motorcycle accident.

What’s more, the majority of “West Coast Bobs” didn’t care to learn about how to properly take care of their own motorcycles. Because of this, the studded leather ‘Eastern Marcels’ doubled down on their leather-clad appearance and DIY attitude.

The American Motorcycle Association & Biker Appearance

While no organizations or publications took an outright stance on whose attire was best suited for motorcycling, the American Motorcycle Association did make it known how they preferred cyclists to dress.

Again, from Born to Be Wild, Randy D. McBee notes that “The American Motorcyclist Association (AMA)…remained committed to its mission of making motorcycling wholesome and argued that any clothing was acceptable as long as it was “clean, neat, and in good taste.”

There was one stipulation, though: “There’s no reason why a motorcycle rider can’t dress in such a manner that he doesn’t seem out of place in the best restaurants, hotels and business places.”

So, as long as you didn’t look grimy, or greasy, or gross, you could wear whatever you liked when you were on your bike…according to the AMA.

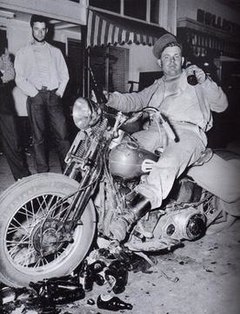

Marlon Brando in The Wild One

Well, things just got more complicated once The Wild One hit theatres in 1953. Brando’s character in the film, Johnny Strabler, was the poster child for the quintessential hardass rebel in early 1950s America.

The Look of the Bad Boy

Prior to the leather motorcycle jacket, denim was the signifier of the “bad boy.”

When Brando wore denim jeans with the leather motorcycle jacket in The Wild One, the two items became synonymous with the calm, cool, rebellious nature of Johnny Strabler, leader of the Black Rebel Motorcycle Club (which, side note, is a great band!). From his studded leather jacket to his rolled Levi 501’s, Brando’s character was the perfect image of the Eastern Marcel.

The iconic leather motorcycle jacket that Brando wore in The Wild One was a descendent of the Schott Brothers original 1928 Perfecto leather jacket.

According to the Schott NYC website, when The Wild One premiered, it apparently caused so much of a stir that the leather motorcycle jacket was banned by schools across the country. The school systems viewed these jackets as the symbol of the “burgeoning teenage demographic, the hoodlum.”

Brando’s Slouch

In addition to his outfit in The Wild One, Brando’s posture was also an iconic takeaway from the film.

Brando had adopted a similar slouch in his portrayal of Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). According to Susan Bordo, “Kowalski’s “slouch” embodied his attitude, which ranged from indifferent to contemptuous and childlike, and was accompanied by a constant and inarticulate “mumbling” and a “smirk”—a physicality and style Brando adopted again for his role as Johnny Strabler, the motorcycle club leader in The Wild One.”

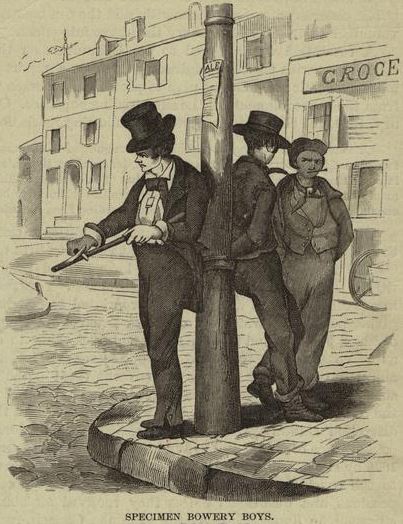

The Slouch of the Bowery Boys

Randy D. McBee, however, notes that the “slouch” wasn’t a new phenomenon that Brando had brought to the world in 1951. His slouch was “… reminiscent of other working-class rebels, like the Bowery B’hoys of New York’s Lower East Side during the nineteenth century and the Mexican American and African American zoot suiters about a century later. They were able-bodied men who were presumed to be unemployed, often linked to gangs and criminal activity, and distinctive for their dress and behavior.”

Proper upright posture was what was expected of a proper gentleman. By challenging the upright ideals of the stuffy, upper class, the middle-class worker was able to establish their own identity and self through their clothing and posture.

The Working-Class Slouch

Both working-class men and women had adopted this type of protest to “defy arbitrary management rules and the monotony of wage labor.” Included with the slouch was the smirk and the mumble. This type of “flagrant insubordination” was a way for men and women to regain their identity, space, and a small amount of control over their otherwise uncontrollable social situation and status.

What’s more, there was actually a functional reason for Brando’s slouched posture in The Wild One. Harley-Davidson motorcycles from the 1940s and 1950s required this type of slouch because of how far back the foot pegs were positioned in contrast to how far forward the straight handlebars were positioned. Talk about back problems! Brando didn’t necessarily create the image of the “biker” as is supposed. Rather, he was a mirror of the public’s image of what a motorcyclist was: some “grease monkey” who was up to no good that wore jeans, a leather jacket, and was in love with his motorcycle to a fault.

The Biker in the 1960s & 1970s

By the 1960s, the image of the lawless, leather-clad Marlon Brando as well as the confrontational, drunk persona of some bikers from the 1947 Hollister rally, was cemented into the general public’s psyche. The feud between the appearances of the West Coast Bobs versus the Eastern Marcels also increased tensions between the public and the biker.

At the start of the 1960s, though, it appeared that the West Coast Bobs were taking over…with the help of some Japanese friends.

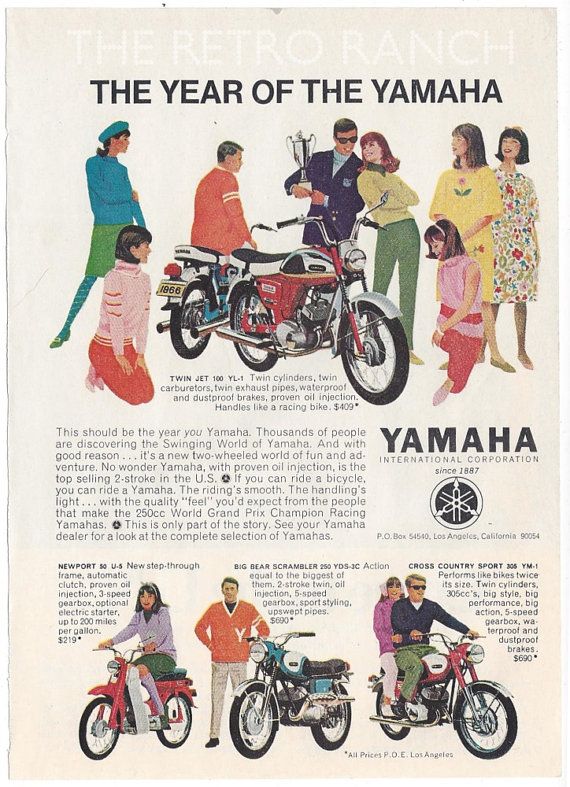

Japanese Motorcycles

With the introduction of Japanese motorcycles, namely Honda and Yamaha, into the American market, the image of the motorcyclist also shifted. The West Coast Bobs were taking over.

According to a 1963 article in Business Week, riders of Japanese motorcycles were trading in the stereotypical image of the “heavy leather jackets,” “goggles,” and “tough young men” for a softer, less confrontational style. These new riders preferred the casual style similar to the West Coast Bobs: Levi’s, a light jacket, and sturdy, but not stiff leather boots.

Because of the introduction of smaller, quieter Japanese motorcycles to the American public in 1967, the motorcycle had become even more popular.

A New York Times article exclaimed: “With the endorsement of doctors, lawyers, teachers, and a wide variety of other professional persons, the motorcycle image has undergone a change that has contributed to the sales explosion.” (Albert G. Maiorano, “A Motorcycle Offers Fun, Thrift–and Respectability,” New York Times, April 2, 1967.)

By 1970, the rate of registered motorcycles had risen to over 1.3 million cycles. By 1971, that rate further soared to over 3 million.

The largely working-class group of riders that had appreciated motorcycles before their popularity, were aggravated by this and began asserting their brand loyalty, particularly to Harley-Davidson. As the premiere motorcycle purveyor, the slogan “You ain’t shit if you don’t ride a Harley” was created. This slogan fueled the divide between motorcyclists who rode American and Japanese bikes.

The Image of the Motorcyclist

Maybe it was because of this new generation of motorcyclists, but the hardcore, true-blue Americans doubled down on their image. The notorious motorcycle gang that was started in the 1940s, Hell’s Angels, have had a sordid reputation since their inception which only got more sordid throughout the late 1960s and 1970s, but that is another matter all together.

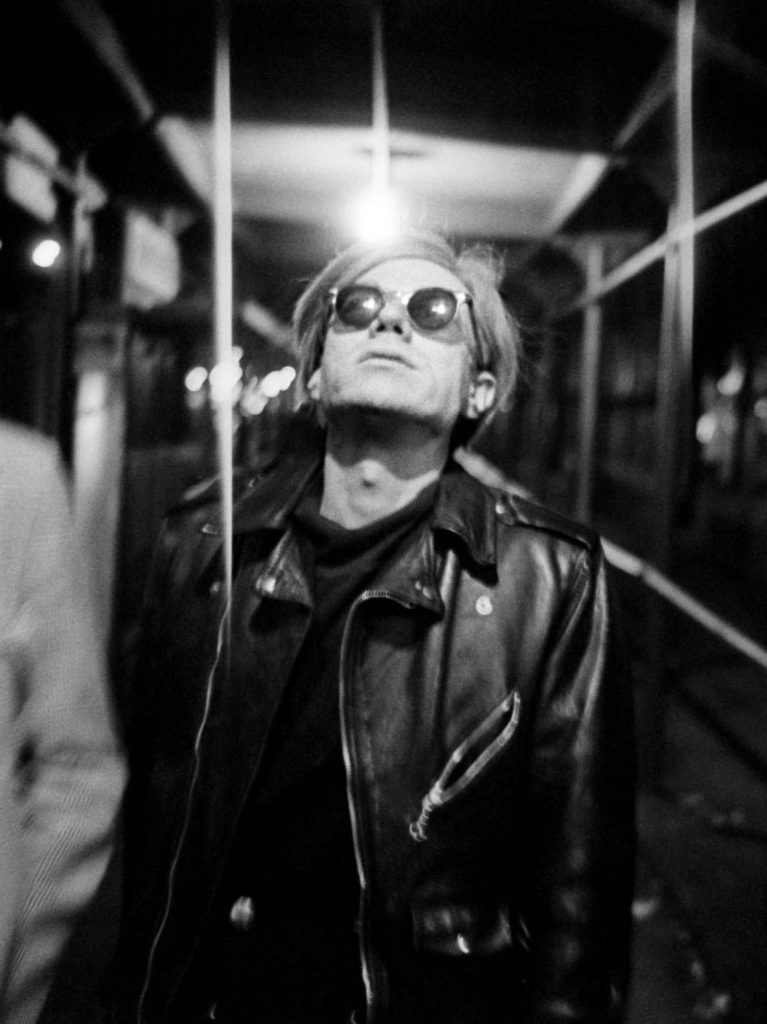

In opposition to the Hell’s Angels, though, influential celebrities of the 1960s, like Andy Warhol, began wearing the leather motorcycle jacket as part of their “uniform.” When paired with a black turtleneck or striped shirt, the motorcycle jacket became a symbol of the über cool, blasé bohemian artist.

This conflict with the image of the leather motorcycle jacket only got more complicated with the tensions between the Mods and the Rockers in England.

The Mods vs. the Rockers, 1964

Even though I’ve primarily focused on the history of the leather motorcycle jacket in America, the clashes between the Mods and the Rockers in Southern England in 1964 were extremely influential in shaping the persona of the jacket in 1970s England which would also influence America’s already complicated relationship with it.

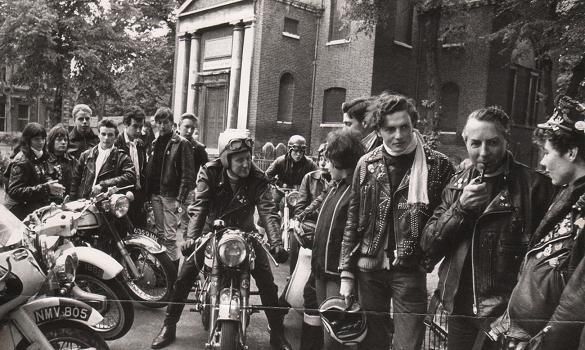

The Mods and the Rockers shared a common love: riding bipeds. Their choice of rides and personal style, though, was very different from one another. The Rockers looked like Brando clones. They wore leather motorcycle jackets, sturdy leather boots, and rolled jeans.

The Mods, on the other hand, looked like the early Beatles. They wore tailored suits, winklepickers (I’ve been obsessed with these shoes since high school!), trendy, tight-fitting clothing, and large olive green anoraks to protect their duds from dirt and mud.

The bikers hated these “dandies on bikes.” Not only did they defy the look of the “classic biker,” but they also rode scooters and scooters were not cool. Scooters were viewed as the feminine opposite of the masculine motorcycle.

Additionally, music was a huge separating factor between the groups. The Rockers favored music from the 1950s, while the Mods listened to new bands, like The Who, Screaming Lord Sutch, and the Yardbirds, among others.

Besides their proclivity for two-wheeled transportation, the Mods and the Rockers had another attribute in common: violence. Both groups were viewed to be incredibly violent by the general public and with good reason!

Throughout the early 1960s, clashes between the two groups would prove to be highly lethal and, in a few cases, deadly. Both groups would travel around equipped with small blades, chains, knives, and other weapons as clashes were inevitable. Since clashes between these groups became somewhat common, they both became viewed as dangerous, though, the Rockers carried that burden given their already tarnished reputation.

Because of this, the appeal of the Rocker image to the growing Punk scene was irresistible.

Punk

Where to even begin?

By the mid-1970s, the leather motorcycle jacket’s reputation was anything but sweet and simple.

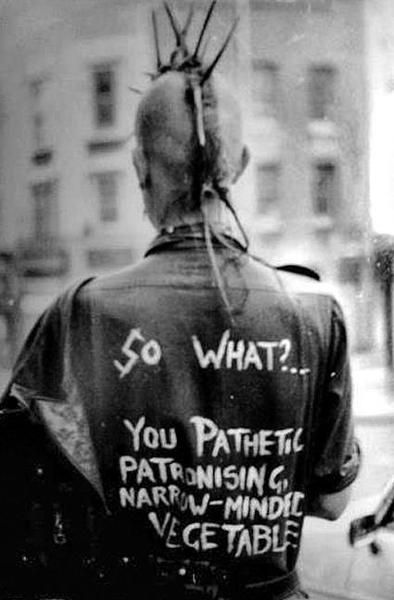

Because of the 1947 Hollister rally, Brando’s hyper-masculine persona on the big screen, the rowdy manner of the Hell’s Angels, the daredevil life of Evil Knievel, and the Rockers who fought the Mods in England the previous decade, the leather motorcycle jacket naturally became one of the defining symbols of the punk movement in England.

This garment signified the restless, agitated, angst that was a cornerstone of the punk movement. And because most punks came from poor or working-class backgrounds, they identified with the DIY nature of early motorcyclists and Brando’s character in The Wild One.

When thinking about punk and its timeframe in the life of the leather motorcycle jacket, we have to take into account the span of time between The Wild One and the birth of punk. The Wild One premiered in 1953. Punk is stated to have been born around 1977. This means that there was a span of 24 years between these two events. To put that short amount of time into context, that would be like someone today bringing back a statement article of clothing from circa 1996 like the suits that Cher and Dionne wear in Clueless (á la Iggy Azalea).

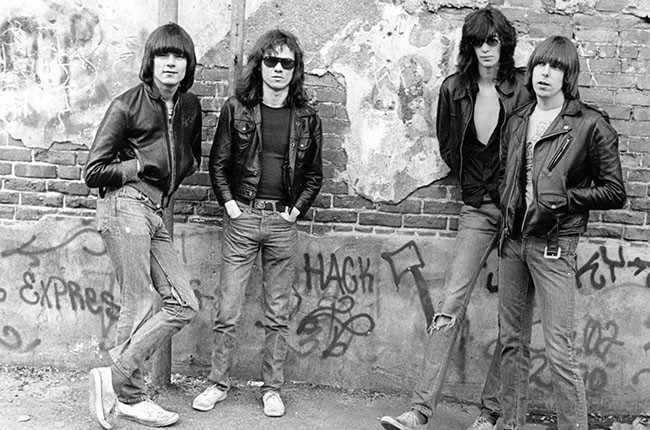

From London to New York, the leather moto jacket was a quintessential part of the punk uniform. A descendant of the original Perfecto was worn by iconic punk bands, including, but certainly not limited to Richard Hell & the Voidoids, The Ramones, The Damned, The Clash, The Misfits, the Sex Pistols…the list could go on and on.

Debbie Harry of Blondie, circa 1978.

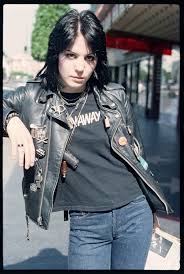

Joan Jett, circa 1977.

This was also one of the first times in its history where women were freely donning the leather moto jacket. Frontwomen like Patti Smith, Debbie Harry, and Joan Jett were fiercely reppin’ the leather moto jacket.

Punks decorated their Perfectos in a myriad of ways. They would attach buttons, pins, patches, or studs, and would modify their jackets using paint, scissors, lighters, or anything else they could think of! The more unique the idea, the better. The whole approach to punk fashion was DIY and making do with what you had available.

The 1980s-1990s: New Wave, Goth Rock, and Grunge…Oh My!

The original wave of punk died almost as quickly as it was born. It was too volatile for the real world. In its place emerged New Wave, post-punk, and goth rock.

The leather motorcycle jacket stuck around through these music movements, but in a different form. Gone was the innovative DIY spirit and the extremely combative nature of the jacket. Now, the leather motorcycle jacket returned to a natural state of wear, mostly void of pins, buttons, or any other types of modifications. Bands like the Jesus and Mary Chain, The Birthday Party, Bauhaus, Siouxsie and the Banshees, The Cure and many others chose the leather motorcycle jacket as part of their uniform.

In the 1990s, Kurt Cobain kept the relationship between the Perfecto and music alive. By pairing the jacket with flannel shirts, baggy, ripped jeans, and large woolen sweaters, Cobain and others created grunge fashion.

The Current State of the Leather Motorcycle Jacket

Fashion is such an interesting, ever-evolving phenomena. The leather moto jacket, as we’ve seen, had such negative connotations around, yet it is no longer frowned upon. It has become an integral part of mainstream fashion.

Also, the overall aesthetic of the jacket has changed quite dramatically. It feels like there are thousands of different styles of the leather moto jacket today. These varied styles play around with the main aesthetic of the jacket, like adding and subtracting zippers, doing away with the bottom belt, removing the lapels, making the lapels larger, doing away with zippers, adding zippers. You name it, you can find it in a leather moto jacket!

Personally, I feel like the leather motorcycle jacket will survive for many, many decades (if not centuries!) to come, but what do you think?

What other fashion items can you think of that used to have very different connotations, but have since become super trendy? Are you a lover of the leather motorcycle jacket? Let me know in the comments below! 🙂

Sources

Maiorano, Albert G. “A Motorcycle Offers Fun, Thrift–and Respectability,” New York Times, April 2, 1967, A27.

McNee, Randy B. “No Worthwhile Citizen Ever Climbed Aboard a Motorcycle and Gunned the Engine, The Rise of the Biker, 1940s-1970s,” in Born to Be Wild: The Rise of the American Motorcyclist, 17-49. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

McNee, Randy B. “You Ain’t Shit If You Don’t Ride a Harley, The Middle-Class Motorcyclist and the Japanese Honda,” in Born to Be Wild: The Rise of the American Motorcyclist, 91-126. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Leave a Reply